7 Years

I had my Leatherman tool, on my belt, for seven years. My soon-to-be-PhD-advisor-at-the-time, Dr. Steven Siciliano, gave me a Leatherman Charge TTi - a top-of-the-line multitool - before my first field season with him and his research group in 2009. He gave it to me around March or April of that year, and I've worn it on my belt nearly every day since then.

That's around 2500 days of that lump of complex, hinged, bladed metal on my left hip. I've gone through three sheaths and I don't know how many subconscious hand-passes over my belt to make sure its still there.

Early this year I accidentally tried to take it through security at Pearson International Airport, on my way to visit Charlie in February. The security personnel were quite nice and polite about it, and let me mail it back to myself in Waterloo; it was waiting in my mailbox when I returned a week later.

At the end of my 6-week-long bookended-by-conferences early-summer-2016 fieldwork I sent it in to Leatherman's facilities in Burlington, Ontario, for warranty repairs. Before I flew from Calgary to Fredericton, I went to Canada Post and sent it to Ontario. Tonight, it has been returned to me.

Or rather, an updated substitute has been returned to me, and my Leatherman is no more. Because the Charge TTi has been replaced in the Leatherman Inc. lineup by the Charge Titanium, that is what I now have. This new Charge Titanium is a thing of beauty, a tool of vast utility that fits perfectly with the accessories (sheath, screwdriver bits) I was instructed not to send in. But it's not my Leatherman (yet).

The knife blade is flawless, not the chipped, scratched, and haphazardously-sharpened blade I used to cut ludicrously-fresh tomatoes and pears on the top of an Arctic mountain.

The saw blade is perfect, not the scratched, difficult-to-open tooth I used to cut branches and an uncountable number of zipties (using the sharp hook on its tip) on seven years of Arctic expeditions and Prairie Rivers canoe trips.

The file - both sides! - is clean to the point of optical illusion along its cross-hatched surface, and bears no trace of the steel soil-gas probes I filed and filed and polished and cursed before fitting their machinist-perfect but field-work-distorted hammer-cap on to drive into the rocky soil of the Arctic polar deserts.

The pliers are smooth and shiny, not the sticking, misaligned grip I pulled endless nails from endless boards with.

Even the scissors, tiny and sharp, are quite excellent, and not the cutters I pushed and squeezed through paper, string, cardboard, and plastic over the majority of a decade.

I'm going to enjoy and appreciate this tool over the next seven years - or more! - but I do feel like an old friend has been lost, and a concrete symbol of my PhD has disappeared.

Thank you, Leatherman, for making such fine tools. I hope my use of this new multitool lives up to the legacy of the previous one. And thank you, Dr. Siciliano, for sending me down this pathway seven years ago.

Showing posts with label Summer 2015. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Summer 2015. Show all posts

Friday, June 10, 2016

My Leatherman

Labels:

Canada,

Field Work,

Grad School,

History,

Life,

Musing,

Reviews,

Science,

Stuff,

Summer 2008,

Summer 2009,

Summer 2015,

Summer 2016,

Sunday Drives,

Travel,

Vacation

Monday, October 12, 2015

The End of (My) Summer

Tomorrow I will pick up my rental trailer, fill it (and my truck) with my abundant possessions, and drive East. This marks the final stage of my move to Ontario - started at the end of March, and I've been between homes (or simply homeless) since then. I measure this by the time elapsed since I last paid rent - unless I find an apartment for half-way through October, I will have avoided paying rent for 7 months by the time this move is complete.

A quick bit of googling (google-mapping?) leads to an estimate of 31 hours total driving time from Regina to Kitchener/Waterloo, taking either of two entirely-Canadian routes that diverge near Nipigon, Ontario. Highway 17 follows the north shore of Lake Superior and around Georgian Bay, while Highway 11 takes an inland route further north. I took 17 the last time I went that way - back in late March. This time I plan to take 11 because there are fewer elevation changes along the inland route. There are a few roads that connect 11 and 17 in their western parts, which will allow me to revisit this decision if, for example, weather conditions at Longlac are very poor.

I received an email from U-Haul today informing me my reserved trailer would be guaranteed available at noon tomorrow, which is later than I'd like to pick it up; hopefully they'll let me have it tomorrow morning. Then I need to pack it and get moving. Kenora, Ontario is approximately 8 hours away, and I am fine with arriving at a hotel in that small city at some late hour. I am also fine with a lesser drive tomorrow, so I might end up merely somewhere east of Winnipeg, or even in that city.

My planned stops - and plans are slippery fish that change and change again - are Kenora, Longlac, and North Bay. That places me within about 5 hours of K/W on Friday. I get a free month of storage with U-Haul, that I have already arranged for a drive-up locker at one of their facilities in Kitchener. Rather than struggle to move my possessions, that I have been apart from all summer anyway, into my friends' basement (up the stairs, through the doors, down the stairs) I can just dump the contents of the trailer and most of what's in the truck into this storage locker and then leave the empty trailer.

If I don't make this schedule I will be disappointed because there are people in Ontario waiting to see me, and a birthday party and other festivities to attend this upcoming weekend, but it won't be the end of the world. Assuming no serious problems on the road, and I fully plan to take it easy and slow, I think I am in danger of losing at most a day, and if things go very well I could conceivably arrive in southern Ontario late on Thursday. Rather than put in a punishing 12-hour day followed by at least an hour to unload, I'm OK with paying for a hotel room in Barrie or wherever if I'm in very good shape as I pass North Bay.

I don't have a picture to go with this post, so here's a shot of the delicious saskatoon-berry pie and coffee I had at Ness Creek back in July.

A quick bit of googling (google-mapping?) leads to an estimate of 31 hours total driving time from Regina to Kitchener/Waterloo, taking either of two entirely-Canadian routes that diverge near Nipigon, Ontario. Highway 17 follows the north shore of Lake Superior and around Georgian Bay, while Highway 11 takes an inland route further north. I took 17 the last time I went that way - back in late March. This time I plan to take 11 because there are fewer elevation changes along the inland route. There are a few roads that connect 11 and 17 in their western parts, which will allow me to revisit this decision if, for example, weather conditions at Longlac are very poor.

I received an email from U-Haul today informing me my reserved trailer would be guaranteed available at noon tomorrow, which is later than I'd like to pick it up; hopefully they'll let me have it tomorrow morning. Then I need to pack it and get moving. Kenora, Ontario is approximately 8 hours away, and I am fine with arriving at a hotel in that small city at some late hour. I am also fine with a lesser drive tomorrow, so I might end up merely somewhere east of Winnipeg, or even in that city.

My planned stops - and plans are slippery fish that change and change again - are Kenora, Longlac, and North Bay. That places me within about 5 hours of K/W on Friday. I get a free month of storage with U-Haul, that I have already arranged for a drive-up locker at one of their facilities in Kitchener. Rather than struggle to move my possessions, that I have been apart from all summer anyway, into my friends' basement (up the stairs, through the doors, down the stairs) I can just dump the contents of the trailer and most of what's in the truck into this storage locker and then leave the empty trailer.

If I don't make this schedule I will be disappointed because there are people in Ontario waiting to see me, and a birthday party and other festivities to attend this upcoming weekend, but it won't be the end of the world. Assuming no serious problems on the road, and I fully plan to take it easy and slow, I think I am in danger of losing at most a day, and if things go very well I could conceivably arrive in southern Ontario late on Thursday. Rather than put in a punishing 12-hour day followed by at least an hour to unload, I'm OK with paying for a hotel room in Barrie or wherever if I'm in very good shape as I pass North Bay.

I don't have a picture to go with this post, so here's a shot of the delicious saskatoon-berry pie and coffee I had at Ness Creek back in July.

Labels:

Canada,

Car,

Food and Drink,

Life,

Stuff,

Summer 2015,

Travel

Monday, September 28, 2015

Field Crews

I really enjoy field work, and if I did not have the opportunity to spend at least part of the year working outdoors I do not think I would have stayed in Science. Field work almost always involves a team of people, for reasons including safety (working alone is verboten by most institutions and organizations, public and private), effectiveness and efficiency, and the realities of funding. Employing* undergraduate students as field assistants for graduate students, post-docs, professors, and other academic researchers has a long history, and each and every time this involves building a field crew, a team of workers to conduct the research, usually for the first time for at least some of the people.

* The

debate regarding unpaid positions for undergraduate students in labs and field

crews is one for another post; suffice to say I am extremely wary of unpaid

work, especially when a commitment of several months is required. This gets to

the heart of several issues in the modern practice of science, and there are no

clear and easy solutions to the problems of getting the work done with very

limited resources.

In my

experience, a professor makes most of the decisions regarding the composition

and schedule of a field crew for each field season. New graduate students are

recruited along with a few undergraduate assistants based on the funding

available and the sometimes-tentative research plans. I have never had any

direct input into the composition of the field crews I have been a part of

during my PhD and post-doc field seasons, though I can think of a few occasions

when I have been offered a hard veto that I have never exercised. I’ve never

had a major problem with any person I’ve been working with under field

conditions, and so far at least I have been able to smooth over or safely

ignore any minor issues that arise.

This topic

unavoidably addresses issues regarding women in science, a huge and very

important topic that certain parts of the blogosphere – at least, parts of the

bits I read on a semi-regular basis – talk extensively about. Most of those

discussions are from perspectives quite different from my own, though our

opinions may align well. In short, I support anybody having a career in science, because I’m having a great time

here and I think lots of other people would, too. There are of course much more

important reasons to support greater equality in science and in other areas,

and I like those reasons, too.

Field work

often includes activities in which a person’s physical strength is an important

factor. Field crews I have been a part of have ranged from mostly-male (Arctic

2010 – 3 out of 4) to mostly-female (this summer, 3 out of 4 for most of the

time). I am the only male in the lab group I am a part of for this post-doc,

and nearly everyone in this lab does at least some field work.

Over the

last few days, and for the next week, I have been working with one other

person, Marie-Claire, a scientist from Universite Laval. She helped me with the

last of my 2015 summer field work, and I have been helping her with some of her

work. She pointed me towards a paper (Newbery, 2003) she read some time ago

that I managed to find during one of our rare encounters with a useable

internet signal a few days ago.

Newbery, L., Will Any/Body Carry That Canoe?

A Geography of the Body, Ability, and Gender. Canadian

Journal of Environmental Education, 2003. 8: p. 204-216.

This is a

paper rather outside my usual academic reading, though not outside of topic

areas I spend much of my time thinking about and talking about. To (awkwardly,

and probably poorly) summarize, Newbery presents arguments regarding the

concept of “strong enough” or “capable of performing that task” that could, and

in most cases should be used as indicators of the suitability for a given

person for a given role or job.

Among the

various things we (“my” field crew) did this summer was boardwalk construction.

Working in a wetland means building places to walk to limit damage to the

vegetation; one of my colleagues quoted his former graduate advisor: “The

boards are to protect the plants, not to keep your feet dry!”. The minimum

boardwalk is literally just a board, something like an 8-feet-long 2x8 thrown

down on the wetland in the direction one might wish to walk. I find this

unacceptably primitive, and prefer something that doesn’t slide away or lever

up and swing sideways when I step on it. Not just to keep my feet dry – I’m

wearing big rubber boots, my feet stay dry regardless – but to prevent

accidents and to prevent a big piece of wood smashing into various bits of

scientific equipment. More acceptable designs include cross-pieces, a bit of

2x4 or 6x6 the walking surface is attached to with nails or screws that helps

to keep the boardwalk in place. In extremely wet areas, where we are

essentially working in a broad, shallow pond with a substrate made of very soft

and water-saturated partially-decomposed organic matter, upright posts are used

to minimize the pumping of the spongy ground that results from a person walking

on the board. We measure gas flux, among other parameters, and pumping the

ground leads to outgassing that invalidates our measurements of “typical” gas

movements. The uprights I have installed this summer are 2x4s cut with a

diagonal end and driven down into the peat.

Sometimes,

an upright can be simply pushed down into the peat, then horizontal boards

attached to it. Most of the time, however, an upright must be hammered down. A

one-handed mallet, such as the 3-pound rubber mallet I purchased a week ago,

works in moderately soft peat but is fairly exhausting where plant roots or

other obstacles interfere with the post-driving. A two-handed hammer, such as an

8-pound sledge or a similar-weight deadblow hammer, is the best way I have seen

to efficiently drive large stakes or posts into the ground. However, while I am

(barely) strong enough to wield such a hammer in the usual manner – swing up

over my shoulder, power stroke with the hammer nearly vertical above my head,

driving down with the bigger muscles of my abdomen as well as my arms and

shoulders – many of the people I work with are not able to swing such a hammer

in that way. Instead, they lift the head to just above their head, with the

handle nearly horizontal, then drive downwards using only the muscles of the

arms. Power correlates very clearly with the speed with which a stake can be

driven to the desired depth, so in some situations I am about twice (or even

more) as fast as my colleagues. Accuracy is obviously important in this task, a

missed stroke might be merely annoying or it could cause a serious injury. So

it is important that one only uses this tool in a way that does not overstretch

their strength or skills.

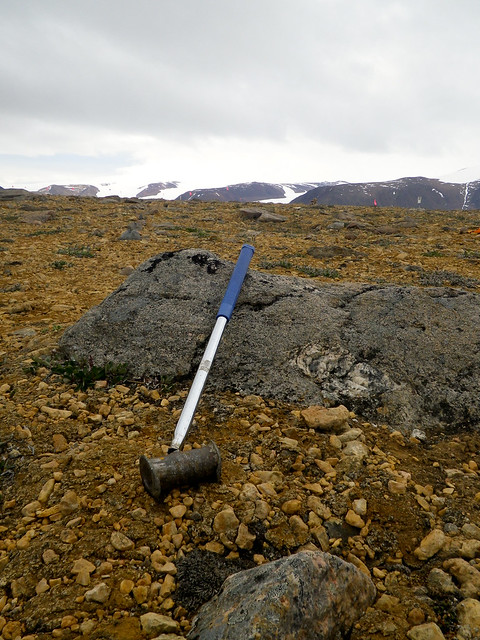

(Picture

unrelated) If you pound enough with a big dumb hammer, eventually it breaks.

Doesn’t matter who does the pounding, hammers have a set quota of bangs they

can handle before they catastrophically fail. This 8-pound deadblow hammer came from Princess Auto with a layer of hard blue plastic wrapped around the metal head. That chipped off over a few days of pounding.

Speed is

probably the least important factor in this task, despite the automatic desire

by anybody picking up a stake or hammer to just blast it out as quickly as

possible. Newbery (2003) speaks of this subconscious urge and spends some time

discussing difficult physical feats and the pride associated with success,

measured perhaps by an ability to complete a task without interruption, or on

the first try. It is rapidly apparent on some reflection that reaching the goal

– boardwalks built to avoid outgassing, canoe and gear transported from one

lake to another – is the only factor that matters (with the unspoken but

important addition that safety – no injuries – comes first [or second or third, if

you’re Mike Rowe]). Keeping the goal in mind, as well as the bigger

picture of both safety and daily, weekly, or monthly work goals, certainly

helps with safety because there is less pressure to rush through difficult

tasks, and makes my life much easier because the attitude towards the work

relaxes, for everyone.

This gets

back to the “strong enough” or the simple binary “capable / not capable” that

Newbery (2003) describes. I can carry two boards over my shoulder; my coworker

might be able to carry only one, cradled in her arms horizontally in front of

her, and she walks more slowly too. No matter, the boardwalk will still go to

where we need it, the work will still get

done, and if I try to do it all myself I’ll burn out or get injured, in

addition to the damaging effects on team morale if I pull some sort of

manly-man silliness.

Newbery

(2003) also briefly discusses the emotional reactions to achievement – if you

think you might be able to do

something, then you do it successfully, it feels pretty good, to over-condense

what looks like a rather sophisticated argument built on philosophy I’ve not

yet encountered. Aside: I think I understood around half of Newbery (2003), the

other half relied on an understanding of current philosophical work that I just

don’t have. Getting back to achievement, I think letting people try, and either

succeed or fail (and hopefully try again!) is far superior to any attempt to

shield someone from something I might suppose they are not capable of doing.

There is almost always more than one way to complete a given task* and I lack

the imagination to instantly think of every possible method.

* Except

the proverbial skinning of a (dead) cat – “There’s more than one way to skin a

cat!” is an ironic statement because really, the only way is to get a firm grip

and pull. That’s something I learned in a 3rd-year Biology lab,

during the requisite cat dissection. We had named the dogfish “Byf” but I

cannot recall the name we gave our preserved tabby.

This

long-ish, meandering post is meant as the beginning of a conversation, or just

a point somewhere in the middle, not my final words on this subject. If you

could point me towards a related discussion happening on a blog or public forum

I would be grateful!

Labels:

Field Work,

Grad School,

Life,

Mildly Political,

Musing,

Opinion,

Science,

Summer 2015

Sunday, May 10, 2015

Summer 2015 Plans

I

successfully moved to Kitchener, and spent April with my friends there. On my

first day at work, we (Dr. Strack and I) worked out plans for the summer that

can be summarized as “Alberta for four months”, so I did not look for an

apartment and just enjoyed the company of my fine friends and their lovely

house in Kitchener.

I am now in

the tiny Alberta town of Seba Beach, about 80km west of Edmonton. I have two

field assistants this summer, Stephanie and Ali, and so far – less than a week

into the season – we all seem to be working well together. We’re living in a

house in Seba Beach rented by the company, Sun Gro, which owns the lease on the

peatlands we’re studying. It very much feels like a summer home, with an

unusual layout – the three bedrooms are on the ground floor, the kitchen and

living room are upstairs – and a clear history of renovation and addition, such

as the electrical subpanel in my bedroom. The furniture is a typical summer

home mix of new and second-hand, but it’s actually a very nice place to spend

time when we’re not working out at the field site.

Our site is

a set of patches of peat wetlands – properly called fens due to their hydrology

– that Sun Gro previously harvested. Some areas were harvested more or less

intensively than others, and some areas have had various restoration efforts

applied to them while others have been left to regenerate on their own. My work

will focus on the nitrogen cycle processes in these ecosystems, especially N2O

fluxes and the mineral and organic nitrogen pools in the soil and groundwater

that contribute to N2O fluxes. Another post-doc,

Cristina, will be working here as well, with her work centred on the dissolved

organic carbon and its relationship to different types of vegetation (mosses

vs. sedges, primarily) and the fluxes of CO2 and CH4.

Data

collection is structured around weekly measurements of greenhouse gas fluxes

with large chambers placed on permanently-installed collars in various places

on the fen. Other measurements, such as dissolved carbon and nitrogen and

water-table height, will fit around that weekly schedule. The workload appears

moderate, which means we’ll have plenty of free time to explore this part of

the world and/or analyze data and come up with fun new research ideas.

Views of our main field site, from our first day, May 7.

I’m also

shopping for a vehicle. I’m currently car-less, again, which is a state of

affairs I always find mildly distressing; I like having my own wheels. This is

Alberta, and for reasons of plans I have in mind for later in the summer, I’m

shopping for a small pickup truck. My modest budget – I could afford up to

about $4000 – covers a range of compact trucks from Ford, Mazda, Dodge, Toyota,

and Chevy with model years from the mid-1990’s to the early 2000’s. I’m

prioritizing 4-wheel drive and a manual transmission simply because I want both

of those features, and I’ve been told to avoid V8 engines for reasons to do

with not completely abandoning any sense of environmental responsibility –

trucks don’t get good fuel efficiency compared to cars as a general rule, but I’m

not supposed to go hog wild here. It seems unnecessary to stuff a big 5L+ V8

into a compact truck, but then I don’t work for Dodge.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)